Two Rebbes from Lodz

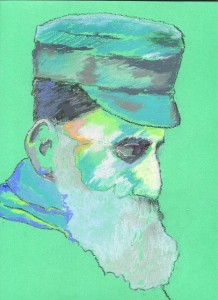

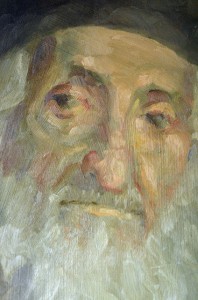

Two Rebbes resided in the town of Lodz, Reb Yankel the Snorer (make no mistake Yankel was no Shnorrer) and his brother, the Alter-Alter Rebbe (the really old Rabbi). The Alter-Alter Rebbe was younger than Reb Yankel but was named the Alter-Alter Rebbe because he was old school, very traditional; set in his ways, unyielding, uncompromising.

On the other hand, Reb Yankel was a modernist, a progressive, a rebel. Howe-v-e-r, Reb Yankel had a problem, he fell asleep at the oddest times, for example during the middle of a sermon – in m-i-d sentence. But that wasn’t the worst of it, when Yankel slept, Yankel snored.

Just this past High Holidays, congregants were listening to Reb Yankel wax on about looking at life in a new way, opening up to new things like automobiles, electric lights, and phonographs. The congregants leaned forward in their seats, ears turned to Reb Yankel as they were intently interested in these new things especially because there were no automobiles, electric lights, or phonographs in Lodz. Where was the sermon going? Where was the world going? Reb Yankel was about to provide the answer when, you guessed it, he dozed off and snored until Erev Erev Yom Kippur.

All the congregants except one left the synagogue after several hours very disappointed and disheartened.

Only one man remained, The Alter-Alter Rebbe. He was accustomed to Yankel’s sudden sleep spells. When they were children, the Alter-Alter Rebbe would see Yankel turn into a statue in the middle of eating chicken soup. The spoon remained suspended in Yankel’s hand for hours and hours.

Yankel seemed to calcify into stone; suddenly he would wake up and continue eating. No one had the heart to tell him why his soup was always cold.

As the children grew, Yankel’s strange behavior became more severe. The sleeping bouts became greater than before. In his early teens Yankel started snoring. As first it sounded like a kitten’s wistful purrs. Over time, the snoring crashed like thunderbolts as walls shook, books fell from their shelves, pots tumbled from the stove. Nothing was safe.

During Yankel’s sleep episodes the Alter-Alter Rebbe thoughts focused on the words l’olam va’ed’ (‘worlds without end’/’forever and ever’) His lips repeated the words over and over and over as Yankel seemed to depart from the world of the living. Not dead, God forbid, but not alive either, just suspended. The Alter-Alter Rebbe voice started soft and would build and build louder and louder in pace with the snoring – in harmony with Yankel’s dissonance, in dissonance with the Alter-Alter Rebbe’s harmony. And suddenly there was silence, silence beyond words, beyond thoughts, even beyond forever and ever.

During the episodes all would have to wait; the Sun ceased in its path, Shabbos was delayed as well as all major holidays, clocks became useless, there was neither work nor no-work. It seemed that candles stop burning in solidarity with Yankel. Even child were not born during the great snores. The Heavens waited, even the Malach ha-Mavis, (may you not be home when he knocks at your door!) stopped his rounds.

After the long pause life would go on. Things begin again, refreshed, whole.

The Alter-Alter Rebbe learnt patience from his brother’s snoring. It was a meditation that would crescendo into the blasts of a thousand shofars, a call for tradition/ a call for change. As Yankel snored the Alter-Alter Rebbe became fixed, satisfied, and strong. Yankel in turn became resilient, transformed and strong.

If we wait, the end of a sentence will come, the soup will be eaten, and worlds will not end.

As for the new inventions, everyone forgot to ask. It was unimportant.

Reb Yankel completed his prayers and walked out of the synagogue with his brother saying “you’re so old fashion.” And the Alter-Alter Rebbe replied, “Hungry for some soup? We need to eat before Yom Kippur, its tradition.” And so they ate.

Itshak’s story

Itshak lived each day under a dark cloud of all encompassing sadness. If it was hard to be a Jew, it was impossible to be a Jew named Itshak from Lodz. Itshak’s portion in life was always less. He defiantly claimed to be five feet tall, four feet eleven inches would not do. God wouldn’t even give him a lousy inch!

No children survived from Itshak’s first two marriages.

Leah, of blessed memory (ז”ל) passed away during childbirth.

The child also expired after six days from a heart defect, before the bris, unnamed, uncircumcised.

Itshak worried about the status of his unnamed, uncircumcised son. Was he a Jew, was he a person? Would God redeem him at the end of days? How do you mourn for such a son?

Itshak mourned ten years for Leah and an additional ten years for his unnamed, uncircumcised son even though the Alter-Alter Rebbe advised him it wasn’t required. Itshak mourned.

Itshak’s mourning period ended.

Hannah, of blessed memory (ז”ל) Itshak’s second wife, tragically died of consumption during their first winter. Itshak couldn’t commence the official mourning period as the ground was too frozen to dig a proper grave. Hannah’s soul lingered on earth for four additional dark days. Four days in which Itshak’s grief only intensified; a grief that was suspended in the sub-zero temperatures of the bleakest days of February, days when the mourner’s Kaddish couldn’t leave Itshak’s trembling lips and enter his anguished heart.

Itshak’s shaking hands covered his tearful eyes. He prayed bitterly, “Jews are doomed to wait. Wait for a messiah, wait for justice, wait for blessings, and wait for the gifts God promised them.”

Itshak mourned ten years for Hannah.

His period of grief ended on his 49th birthday. Itshak longed for happiness; his period of exile should end.

—-

Revka was Itshak’s third marriage professionally arranged by Yidel the matchmaker.

Itshak remained apprehensive when Yidel mentioned the prospective young bride. How could it be that her family would be interested in poor Itshak? He was middle aged; married twice, perhaps cursed, not the best future for an only daughter.

Was an Evil Eye casted upon this forlorn man?

Yidel insisted the marriage was meant to be, Itshak would be a fool not to marry Revkala.

Revkala’s papers avowed she was eighteen years, daughter of Wolf ben Yakov and Gittel bat Ester. She was more likely sixteen or fifteen – a young girl, a good woman. She was born on a farming commune near Ekaterinoslav, a place not noted for precise record keeping, especially regarding daughters. Yet, how could one forget a child’s birth date? Wasn’t the day as blessed as the day of creation itself?

Revkala’s parents gratefully agreed to the union. They reasoned Itshak must be a Litvak, who else could afford a professional matchmaker? They saw Itshak as Revkala’s best hope for a better life; as the expression goes, better marry a poor Litvak than a poor Galitzianer.

In reality, Itshak was really poor and a really a Galitzianer.

The matchmaker impressed on Itshak that he should grab this one and over look the defect. Yidel insisted, “Little Revkala will make you a happy man, YOU DESERVE HER, she is a lovely girl” And then like an experienced salesperson she whispered, “You’ll hardly notice the defect, look at her beautiful picture”. Itshak stirred at a two inch square scratched photo of Revkala, tears welled up in his dim eyes and dropped on the photo blurring the defect.

Itshak weighed the options, although when there is only one option there are no alternatives. The choice was made. She would be his best chance for happiness.

Revkala, God willing, would provide Itshak a progeny. On the other hand there was that unknown defect. Was it her nose, her eyes, her ears? Or perhaps her heart, he could not bare the thought of such a defect, not again. But Itshak was lonely and could not grief his whole life.

Itshak paid Yidel 120 kopeks, four hens and a train ticket to return home. This was his whole life’s savings. The deal was closed and sealed. Yidel returned 18 kopeks and one hen as a wedding present.

Did I mention that Itshak was blind in one eye and only saw shadowy images from the good eye?

—-

Itshak and his young bride of three months, Revkala walked in the autumn rain from Simchas Torah services. Unknown to Itshak, Revkala was pregnant.

Revka experiencing morning sickness, hesitated revealing the simcha to Itshak, what if it weren’t true, what if God forbid, she miscarried. She agonized if he knew he would worry that he’d cause an impending tragedy, God forbid.

Revka loved Itshak too much (a bride of only three months) to hurt him. Hadn’t he witnessed enough grief? Even if it would provide great happiness, how could she burden Itshak? And what if the defect was passed on?

Revka fantasized of returning home, waiting until the baby was born then return to Itshak reuniting the new family. He would understand. If only she had the means. It was not possible.

As they walked up the broken sidewalk on Wolborska Street, Revkala tripped on the loose gravel. Her frail body was about to slam against the hard concrete. A feeling of unimaginable angst shook her very being.

Itshak, not knowing why, leaped ahead of Revka catching her before she fell, a fall that would have ended his unknown and unborn hopes and dreams. Itshak sensed that the place was holy.

Itshak gently steadied Rivka’s body.

Off in a thicket, Itshak noticed a wild goose. He grabbed the foul, twisted the life from its neck and offered it to God without question, without understanding.

That spring, a baby girl was born to Rivka and Itshak. Itshak noted the date (in Russian, Polish, German and Hebrew). His grief ended. He never knew what the defect was or if one ever existed.

Itshak, of righteous and blessed memory (זצ”ל) lived to one hundred and three. Revka and Timnah mourned his passing for ten years.

The Minnas of Lodz

The Lodzer Rebbe was known to have said that the Alter-Alter Rebbe said to his brother Yankel when Yankel was not snoring, “Truth sometimes comes from misunderstanding, misunderstanding doesn’t come from truth, never…not even once”.

Minna was the most common girl’s name in Lodz, but it wasn’t always so. Jochim the Counter (known for counting everything that needed counting) examined the 1912 All-Poland Census establishing that 1,098 of 1,142 newborn girls were named Minna, the balance (44 according to Jochim) were named Annim as some parents figured that Polish like Hebrew is written right to left. The name was rarely seen a decade earlier as the 1902 All-Russian Census certifies that the name only appears twice and is spelled Minneh in Cyrillic characters.

Not since the time of Alexander the Great[1] did a name become so fashionable so fast.

Why did Minna become so popular? It wasn’t because of the traditional practice honoring a deceased relative by giving a son or daughter the relative’s name, most parents never had a relative name Minna. The Minna frenzy was the result of a misunderstanding. The craze can be pinpointed to May of 1906, when the first Minnas were named.

May, 1906

Minna bat Revka’s identification papers recorded her birth date as 14-May-1906. Her family dwelled at Spacerowa Street 12b.

Minna bat Sarah was born on 16-May-1906; her family resided at Spacerowa Street 12c.

Minna bat Lena – 18-May-1906, Spacerowa Street 12a.

So we have the three Minnas of Spacerowa Steet.[2]

Over time more and more Minna’s were brought into the world as the commandant be fruitful and multiple was strictly observed.

Since each baby girl had the same name things became rather confusing. To maintain order, parents identified the different Minnas by the families’ apartment number. One Minna was Spacerowa 12b, another Krawiecka 14a, and another Drewnowska 8e and so on. The practice became routine, some rabbinic authorizes insisted this was required, a matter of Jewish Law. As with any questions of Law, issues were hotly discussed and debated.

When there is such a great question, the Jews of Lodz did what Jews do everywhere; they chartered an organization; The Institute for the Propagation and Regulation of the Name Minna, IPRNM would deal with the questions resulting from the name. Without delay several competing and differing organizations were also founded. They split into other organizations.

April, 1906

The three expectant mothers sat on the edge of their seats sipping weak Floral Peacock brand tea. They gathered at 12a (the apartment not the Minna), a ritual they did each Tuesday mid afternoon. As they read the daily paper each mother searched for a name for their soon to be born child.

If it’s a boy Avraham, Moshe, or Dovid, or Yankel or Yossel, Yakov, Yonah, Zora, hundreds of possible names, names of relatives that passed away, uncles, great-uncles, brothers, grandfathers, great-grandfathers, Jewish heroes of the past, names of famous Rabbis and scholars, names of famous secular Jews, names, names, names. But if the baby was a girl there was only one name that would honor their town and all Jewry. For weeks the newspapers ran articles about the name.

January, 1906

Velvel hammered the last nail affixing the mezuzah to the doorframe of Spacerowa 12 when his hand slipped; the hammer smashed the case of the new mezuzah to pieces. He caught the miniature holy parchment scroll in mid air as it sailed out of its container. God forbid it would have fallen to the dirty front stoop. Velvel kissed the parchment, checked that it was not damaged and thanked God that he would not have to fast for 30 days, the penalty for dropping a holy scroll on the ground.

Velvel cursed the hammer for smashing the mezuzah.

At that very moment he noticed another very small scroll resting inside the shattered mezuzah. It was the size of a postage stamp with words written in an unusual script. Velvel held the small scroll close to his eyes, and then extended his arms far from his body trying to bring the words into focus. He repeated this exercise over and over then added squinting, turning toward a street light and away from the light. For some unknown reason Velvel also squatted to the ground followed by standing on his tiptoes, he turned left and right, closed his eyes and opened them, covered his ears, held his nose, opened and closed his mouth.

None of these actions revealed the message on the tiny document. Velvel concluded that it must be written in a very ancient Hebrew script. He theorized that he found a lost Holy Book even if it only was the size of a mere stamp.

Velvel would be famous, honored and lauded, perhaps his face would appear on a coin or postage stamp itself, and at the very least his discovery would be featured in the local newspapers. It would be the talk of Lodz for months, years!

He carefully placed the scroll in a cigarette case he carried in his shirt pocket, closed the case and slid it deep into the pocket. His right hand stayed buried in the pocket to protect the holy book. Finally, Velvel for good luck again squatted to the ground followed by standing on his tiptoes; he turned left and right, closed his eyes and opened them, covered his ears, held his nose, opened and closed his mouth. He adjusted his pants and started walking with upmost determination.

Velvel marched to the Lodzer Rebbe to make known the artifact, on route he stopped at four newspaper offices, three yeshivas, and a bathhouse, he wasn’t sure why he stopped at the bathhouse.

Finally, late afternoon Velvel arrived at the Lodzer Rebbe’s House. On seeing the artifact, the Lodzer Rebbe almost fainted. He too held the precious scroll inches from his eyes followed by extending his arms far from his body. He paced in a circle first counterclockwise then clockwise. He put his glasses on and off from his face several times, scratched his forehead, held his chin, buried his face in his two hands, closed his eyes, opened them and was silent for several hours. Velvel remained silent as the Lodzer concentrated all his might on the scroll.

Soon after Midnight, the Lodzer finally said, “I believe this is a lost holy book”, look here it appears to say, “And Moshe had a sister, not Miriam, the other sister Minna. Minna was messy; however she was also a kind soul”. “There is more, but I can’t decipher the words. We need to send the scroll to Reb Grosser in Yerushalayim.” The Lodzer informed Velvel that the great Rabbi wrote many books about the possible existence of Moshe’s having second sister!

The Lodzer advised Velvel not to tell a soul about the scroll, to keep it secret. Regrettably, Velvel forgot that he had already visited four newspapers, three yeshivas, and the bathhouse.

Rumors where everywhere, Velvel found the lost tribe, he found the Ark of Noah, he found Mount Sinai, he found the lost tabernacle, he found the holy stone tablets, he found the afikoman that his neighbor Jose hid and never found, maybe he found Smuel’s eyeglasses, or he found a new road to Lublin that shortened the trip by two hours.

Jews loose lots of things, more than most people.

Lodz was abuzz with rumors for weeks. Velvel had to set the record straight. He visited the editors of the four newspapers, he meet with the Rosh-Yeshivas from the three Yeshivas; he even went back to the bathhouse. At each place he told the story of his discovery. “I located the Scroll of Minna, the messy sister of Moshe, the nice one, the other sister, not Miriam.” Velvel’s story appeared in the local papers, on billboards, it was even embossed on all outbound mail. The world needed to know!

Much commentary was written on Minna. Why was she messy? Was she nice and Miriam mean? Did she accompany Moshe across the Red Sea? Who was her husband, did she marry? Did she have children? Many questions needed to be answered.

One thing was certain; Lodz would be the New Jerusalem of Poland. Vilna, their rival would finally play second fiddle.

As weeks and months passed, the town leaders recognized this was a gold-mine, bigger than anything that had ever happened before in Lodz. A decree was issued by the town elders. It encouraged the promotion and use of the name Minna for all girl children.

March 17, Erev Erev Pasach, 1907

A letter arrived from Eretz Yisrael. The Lodzer Rebbe sat in his study hands trembling. After several hours he slid his letter opener across the back of the envelope. In it was a brief note from REB GROSSER, it said,

My dearest Lodzer Rebbe,

Hope you are in good health.

The document you sent he is a cancelled stamp from Tsarist Russian. New it is worth two kopeks, as is, nothing.

Have a Good Pasach!

Yours Truly,

Reb Grosser

PS – Please send another jar of those pickled tomatoes you so kindly provided last year.

The use of the name Minna declined over the next few months. On a positive note parents stopped identifying their children by apartment numbers.

Timnah’s Story

It is written: And Samson went down to Timnah,and it is written: Behold, thy father-in-law goeth up to Timnah! R. Eleazar said: Since in the case of Samson he was disgraced there, it is written in connection with it ‘went down;’ but in the case of Judah, since he was exalted in it, there is written in connection with it ‘goeth up’. R. Samuel b. Nahmani said: There are two places named Timnah; one [was reached] by going down and the other by going up. R. Papa said: There is only one place named Timnah; who came to it from one direction had to descend and from another direction had to ascend, as, e.g.,[if one approaches Timnah from] Wardina, [or one approaches from] Be Bari and the market-place of Neresh.– Babylonian Talmud: Tractate Sotah, Folio 10a

38:13 בְּרֵאשִׁית

וַיֻּגַּד לְתָמָר, לֵאמֹר: הִנֵּה חָמִיךְ עֹלֶה תִמְנָתָה, לָגֹז צֹאנוֹ

Gen. 38:13 ‘And it was told Tamar, saying: ‘Behold, thy father-in-law goeth up to Timnah to shear his sheep.’

Timnah Yakob a butcher by trade hadn’t slaughtered for months. Nor had he eaten beef or chicken since the occupation. For weeks, the only food available was scraps of crusted bread; then none. The motzi (prayer for bread) had long ceased to be heard.

Timnah approached the old Jewish Cemetery from Aleja Glówna (the main alley way). He paused prior to entering the sacred grounds. Clinging vines overran the entrance’s green iron gates. Vines that were attempting to escape the cemetery boundaries, freeing themselves from death and despair. The crossbars impeded their longing for freedom. Even vines were prisoners in the encampment called Lodz.

Timnah intensely gazed at the gate, a place that he passed a thousand of times, a place that was inconsequential before. He stood there as if for the first time, a lost tourist in his home town. He looked upward; his eyes attentively scanned the massive iron doors. They traced the ornate mortar and brick arch and rested on the Mogan Dovid that crowned the structure. His oppressive despair dissolved for the moment, a moment that he wished would never end.

For Timnah the Mogan Dovid proclaimed, Jews are here. It simultaneously separated and united.

As he looked up, light emanated from the angular iron intersections, everything inside and outside of it blackened and vanished. Timnah was drawn into the symbol. Up and down, left and right lost meaning. Like Jacob’s angels, Timnah’s eyes descended and ascended the rungs of the Mogan Dovid.

The symbol was everywhere; on cemetery gates and tombstones, synagogue facades, sacred books, embroidered Torah covers, flags and banners, on mezuzahs that adorned doorposts and graced necklines, on butcher shop windows, on emblems of social welfare agencies, on Zionist and Bundist flyers and manifestos.

It appeared on the pages of the seven daily Yiddish newspapers, it was used by groups on the left and on the right, on the far left and the far right, by those who feared and those who despised.

Timnah despised it.

The local Polish officials zealously enforced the orders of their German masters. They taunted Jews to cut the crude yellow badges from patches of cloth. In an act of unimaginable cruelty, Jews were forced to buy the material from them, material with the stench of urine.

The symbol was worn next to bruised hearts. For Timnah it marked a second circumcision; a warning. It was a proclamation and a burden of identity.

The cemetery-gate marked a place of transition, both an entrance and an exit where direction lost meaning. It separated sacred and worldly, the known world of sorrow and despair and the world beyond; a place where butchers became poets and poets committed suicide.

The greatest sins are committed as a result of unimaginable despair. He longed to merely escape the tyranny even if for one day, to see one starry night.

Blinded by tears, Timnah leaned against the central pillars of the cemetery gate; he lacked the strength to pull them down. His butcher’s knife performed a ritual circumcision of the heart that ended his unimaginable despair.

Momentarily Timnah’s first and final poem protected inside a small oddly shaped envelope, clung to the tangled vines that encircled the iron gates. An unexpected wind expelled it skyward. The envelope hovered over the Ghetto wall without a care, like a child’s balloon. Finally a second gust swept it into the night sky as it disappeared into the infinite darkness.

Yankel’s grandson Shimshon found the odd envelope on the forest floor; it was carefully folded into a makeshift six point star. He hid it in his torn shirt pocket, the pocket next to the heart, the one with the faded image of a Star of David. The wind propelled Shimshon forward, he ran for hours into the heart of the forest.

Shimshon reached a small clearing softly illuminated by star light. Extracting the envelope, he carefully unfolded its tucked corners. Inside was a tattered yellow cloth. On the reverse side, the hidden side, the side that faces the heart was the words:

Timnah’s Proclamation

L’Chaim! How, especially now

Shema

God hides His face away

Yisrael

The Cemetery Gates summons

Ado-shem

As life and death stand too close together

Elokeinu

The oppressive Ghetto walls

Ado-Shem

The deeply carved foreheads lines formed by unyielding despair

Ehad

Sorrow of imprisoned vines, enslaved souls

Unimaginable despair

Star on a tattered shirt

Stars in a night sky, I long for you

Amen

Lemech’s Folly

…19 And Lamech took unto him two wives; the name of one was Adah, and the name of the other Zillah. 20 And Adah bore Jabal; he was the father of such as dwell in tents and have cattle. 21 And his brother’s name was Jubal; he was the father of all such as handle the harp and pipe. 22 And Zillah, she also bore Tubal-cain, the forger of every cutting instrument of brass and iron; and the sister of Tubal-cain was Naamah. 23 And Lamech said unto his wives: Adah and Zillah, hear my voice; ye wives of Lamech, hearken unto my speech; for I have slain a man for wounding me, and a young man for bruising me; 24 If Cain shall be avenged sevenfold, truly Lamech seventy and sevenfold. – Genesis 4:19-24

Lemech’s Shame

It was a vague memory, veiled in shadows; one the family preferred not remembering but could never forget. Lemech’s ancestor, Kayin, committed that terrible act, the murder of his own brother. It was so long ago. Was it possible Kayin was still alive, a cursed fugitive who wandered from town to town longing to become anonymous?

His face forever betrayed him; it confessed his sinful deed without words, by sadness alone.

Lemech’s Sin

Lemech specialized in ancient Greek and Roman antiquities. He acquired an extensive catalog of miniature gold and silver statues and figurines; ancient gods and goddesses. They were easy to transport as he traveled the capitals European. Lemech’s clientele included princes and kings, bankers and the nouveau riche, even the Holy See. This was remarkable for an individual of humble origins whose very name was rooted in poverty.

As blessed as Lemech was with financial success and security, he was miserable, never content, never satisfied. As his wealth increased he became more loathsome. He was unfaithful, neglected his children, and was not to be trusted.

Lemech had long abandoned decency. When asked to contribute to the victims of the pogroms after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II, he refused. It could hurt a pending business deal, the sale of a collection of Greek figurines destined for the Hermitage collection. The figurines were used by the Greeks as amulets to ward off catastrophic events.

Ada’s Life

Ada, a faithful wife bore Lemech two sons, Yaval and Yuval.

She was the daughter of a celebrated hazan (cantor) from Kovno. Ada inherited a beautiful voice. She lacked physical beauty. She was overweight, short, wore a severe expression, developed varicose veins and suffered from swollen feet. Lemech cruelly ridiculed her appearance and teased her at every opportunity, publicly and privately.

Over the years, she grew accustomed to his harsh treatment. Beatings were tolerated, abuse was accepted. She suffered by staying, and would suffer more if she left. Ada held fast to a memory, a phantom; a husband who would never return. Remaining silent was more tolerable than the alternatives. Like a deer about to be felled by a gunman’s bullet, she waited for her fate. It never came.

Lemech pursued his deceitful ambitions without constraint, including becoming an apostate to please his patrons while advancing his business interests. He disgraced and humiliated Ada and her family, a family blessed by six generations of righteous Jews, rabbis and cantors, cursed by deceit. The disgrace increased twofold as her older son, the first born, accepted the baptismal waters. Ada sat shivah, mourning her losses.

Yaval’s Sin

Yaval, Lamech’s oldest son was a handsome untamed youth who worked in the family business. Like Lemech, he was tall, untrustworthy, and immoral. He cheated his clients and friends. He boasted about promiscuous exploits, of the hearts he broke, of patrons he cheated. Yaval, an unrepentant philanderer and liar, lacked redeeming qualities.

Zila’s Sin

Zila, Lemech’s mistress, remained in the shadows; a family secret.

Zila was exceptionally beautiful, comparable to the bronze images sculpted by Praxiteles. Her skin was dark, the hue of Turkish coffee. She had a soft alluring complexion with lavender highlights, exotic black eyes, shimmering black hair, strikingly elongated features, an enticing neckline and receptively seductive breasts. There was an aloof aristocratic air about her, revealing little beyond her outward beauty.

Zila kept an apartment in an affluent district near the Jewish Cemetery on Bracka Street. She was barren, and lacked family at least in Lodz. She never worked. She was a person without a history, without a past, future or present. Lemech was her financier, her sole contact with one exception.

Once, a young attractive girl, mysteriously arrived by train from Istanbul, visited Zila and departed the same day. This was their only encounter.

Yuval’s Voice

Yuval was a sensitive individual, born with a cursed skin condition; he stayed in the shadows away from the Sun finding solace in music. He was drawn to the piano resulting from a chance meeting of the virtuoso pianist Franz Liszt.

Liszt was stranded in Lodz due to an unexpected winter storm while on route to Warsaw. Lemech instinctively sensed a business opportunity. He also knew Liszt was passionate about building an art collection.

Lemech contacted Liszt’s agent insisting the virtuoso spend the night at Lemech’s home. Desiring to impress his guest, Lemech rented the finest piano available in Lodz, an 1846 Bösendorfer.

Liszt reluctantly agreed to spend the night. After an eloquent dinner party, he gave a private performance of his not yet published Transcendental Etudes. Lemech had little interest in the music, instead schemed to sell Liszt a bronze bust of Beethoven of dubious provenance.

Lemech’s scheme inadvertently awoke in Yaval a love of music. Yaval was profoundly drawn to it. Liszt, seeing the response, inspected the youth’s hands, advising Lemech Yuval’s long fingers were well suited for the piano. He knew the boy’s temperament was also well-matched but kept it private. There was no point in revealing too much.

Liszt insisted, “Allow the boy to study piano, he will develop into a formidable artist.” As part of the deal, Liszt purchased the over priced Bust of Beethoven with the stipulation that the piano never leave the house and Yuval be provided the best music teacher available chosen by Liszt himself. Lemech accepted the terms, at least for the while.

Yuval was to be a gifted musician. He had a profound sensitivity for interpretation, his playing was exquisite. For Ada, the music provided an escape from Lemech’s cruelty; it was the one thing in her life that had beauty and meaning. Ada, inspired by the music, started to sing songs from her childhood to Yuval’s accompaniment.

Yaval despised the attention Ada lavished on Yuval. Yaval’s accomplishments seemed unimportant by comparison, his pursuits shallow, superficial. Yuval’s music comforted Ada especially as Lemech withdraw. Hidden tensions increased.

Zila’s Hope

“Unknown to Lemech, Zila stopped taking the concoction that kept her from conceiving. She secretly longed for a child, an unspoken yearning. Lemech learning about her pregnancy became enraged. She would certainly lose interest in gratifying his needs and desires.

Zila gave birth to Tuval Kahan. As the years passed, Lemech’s anger never diminished.

Tuval Kahan’s Story

Tuval Kahan was exceptionally strong. He worked as a blacksmith fashioning weapons of iron and silver. His name became synonymous with highly prized military swords. They graced the uniforms of officers from rival armies. Commissions arrived from the Tsar and the Kaiser, from generals and kings.

Tuval did not know his father. Zila also kept silent about his identity; her whole life was veiled in secrecy. It was just one more thing to keep hidden.

Approaching old age, Lemech felt compelled to reveal the truth, embrace Tuval Kahan. It was time to atonement, right this wrong.

Lemech entered the blacksmith shop transfixed by the deafening blows of the blacksmith’s hammer as it struck the anvil ablaze with fire. The flames howled as if searching for something or someone to consume. Did they decide on their own to leap into Lemech’s grief-stricken eyes? The old man screamed in agony. Cold water poured down his face from the bucket Tuval Kahan held in his trembling hands, but it was too late. Lemech would never see his son nor make amends.

Yaval’s Treachery

Yaval, like his father, held grudges. Yaval envied his brother’s fame; Yuval became a celebrated pianist, touring the concert halls and palaces of Europe. Yaval decided he needed to take revenge against the entire family. A devious plan seasoned by Yaval’s years of ruthlessness and treachery fermented.

He would stage an accident and make it look like Lemech was the conspirator, Tuval the victim. The plot would pin the blame on Lemach. After all, hadn’t Lemech recently visited Tuval’s shop, a visit that ended in tragedy? Lemech would surely take revenge. The plot would also punish Yuval.

Yaval know Lemech would be home that evening; he had few options due to his blindness. After the accident, Yaval would spread a rumor that Lemech hired Tuval to move the piano from the house, Lemech would be blamed.

Yaval’s plan proceeded. He recruited Tuval to move a heavy object. Yaval promised to help and agreed to pay Tuval handsomely.

Tuval Kahan arrived at 77 Bracka at the appointed time. Yaval motioned at the grand piano, the object to move down two flights of steep stairs. Tuval was confident with Yaval’s help they would be able to move it to its new location on the first floor.

Yaval positioned himself at the rear of the piano. Tuval balanced the piano on his thighs as his legs straddled the stairs. Once Tuval was in a vulnerable position, Yaval released his grip knowing Tuval could not possibly manage the piano by himself. Tuval struggled under the oppressive weight; he screamed for Yaval to return, Tuval cursed the deceitfulness.

Lemech’s Dream

Lemech was fast asleep in his room; as he dreamt he lamented his life. He sensed a tragic ending was soon at hand. Would the letter he wrote so long ago announcing his confession and fears be found after his death? Would it merely vanish like his wasted life? It was written before his blindness, before his conversion, before his greed, before his infidelity, before his sons, when he loved Ada. He always feared his fate was sealed by the misdeeds of an ancestor so long ago.

The piano was tittering precariously on the steps as Tuval continued to try steadying it. Lemech awoke from the commotion. He awkwardly approached the stairs, his hands trembling to find the rail in complete darkness. Lemech lost his footing plummeting down the stairs. He crashed into Tuval causing Tuval to loss his grip. The piano tumbled down the stairwell crushing Tuval and Lemech in its wake.

As the piano descended, it gained momentum breaking into small pieces as a cacophony of sound emanated from the shards, splinters and strings. The sound increased in volume as if the piano seemed to be releasing years of oppressed emotion and pent up anger.

Yaval stared down the bloody stairwell pleased at his handiwork. The plot worked better than he had anticipated. Suddenly a hand pushed Yaval from beyond. He lost his balance plunging down the stairs. His neck snapped during his descent.

That very moment an elderly man happened to walk in front of the doorway. He was caught in the wave of debris, becoming the final victim from the carnage, a strong winter storm ensued.

Release

As the storm intensified, a letter tucked in a waterproof tallis bag, once secretly placed inside the piano’s cavernous frame, freely blew across Bracka Street, over the cemetery grounds, eventually landing in the turbulent waters of the Pilica River.

That night, Ada left Lodz, walked near the city gates for the last time, crossed the Old Pilica Bridge to the train station on a journey to be with her son, her only son, Yuval. She noticed an odd cloth bag floating near the bank of the river. As she bent over to inspect it, she observed her name embroidered on it in ornate red letters. She picked up the bag placing it in her inner coat pocket, the one opposite her heart.

…and Renewel

Yuval did not know about the accident. Days before, he left on a journey to Vienna to pay homage to the late Franz Liszt. Yuval prepared the Transcendental Etudes as a music tribute to his friend and mentor. Afterwards Yuval would travel to the Ottoman Empire for a private concert honoring of the marriage of Sultan Mehmed to a young bride.

Ada arrived in Istanbul ready for her new life. Mother and son reunited.

That evening she sang as Yuval accompanied her in celebration of the jubilee year, a year of forgiveness, release and hope.

Naamah, the daughter of a prostitute, listened attentively, seated next to an adorning Sultan.

[1] After the death of Alexander the Great in 356 BCE, it became mandatory that every new born Jewish boy in Alexandria be named Alexander; parents quickly consented to this rule as the penalty for naming a son anything else resulted in cutting off the father’s member. There was 100 percent compliance with the rule. Alexander was a very popular name for a long time.

[2] Jochim claims to have firmly established that the Minnas of Spacerowa Street 12 were the original Minnas of Lodz. His findings are disputed by the Minna Research League (an orthodox organization) and by the Jewish Given Names Bureau, Minna Subcommittee (a progressive organization). The two organizations agree that Jochim was wrong yet disagree on the details, repercussions, and religious obligations.